When is a bear, not a bear? Answer when it is a Jungian archetype!

If you were Sioux, a bear was someone who, over generations of observation, had acquired a cluster of characteristics from which one could learn. In their own right, they were intelligent creatures adapting to their world, living their own best life. A bear might choose to befriend you, possibly as a result of your beseeching, coming to you in vision and dream, one that might yield real-time effects - a healing song, say, or a new herb for a particular ailment, even self-decorating tips (for bears like to paint their faces with colored mud).

What a bear would not be would be a symbol generated from your own projecting consciousness, or, for that matter, as an animal, an inferior being. It might be true, as in Christianity, that humans were created last for the Sioux but this did not make them the apex of evolution (as they were in Jung's evolutionary frame) but the youngest and most foolhardy creatures in need of teaching support from the surrounding hosts of other animated persons (that might include plants or particular stones)

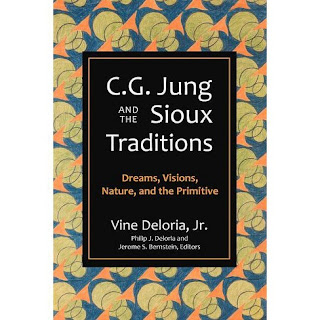

If this illustrates the sharp contrast, the Indian activist and scholar, Vine Deloria Jr. draws between indigenous traditions and the thought of C.G. Jung, you might imagine that the dividing lines of Deloria's critique are so strongly drawn as to be wholly negative, indeed one might think (from a Native American perspective) why bother? But Deloria's book is a good deal subtler and compelling than this. For Deloria Jung is a bridge, the best available bridge, between 'Western thought forms' and the Native American. It is a bridge worth describing, and potentially building upon.

Yet of which Jung are we speaking? Are we encountering the Jung who was so emotionally compelled by his brief visit to Taos (and its pueblo communities) that he maintained a continued interest in Native Americans, with which he continued to pepper his talks and essays with insightful, highly intuitive, often admiring asides, or the more public Jung, a man of his time, aiming to be as scientific as possible even though his science, even then, might be thought limiting, and which now may often have been superseded even on its own terms?

Deloria patiently describes and contrasts both Jungs and places them alongside his own Sioux tradition to illuminating effect.

For example, he explores the vexed term ''the primitive" with two chapters describing both Jung's negative and positive use of the terminology. Since Jung was thinking in terms of cultural evolution (and of consciousness), ofttimes indigenous people (as markers of primordial people) are seen as negatively backward, immersed in Levy Bruhl's 'participation mystique', unconscious, navigating by instinct, and hardly separable as individuals. But, at other moments, usually when Jung is setting aside his framing and relying on his own, and others, closer empirical observation, he recognizes the positive 'primitive' a highly adapted and adaptable community, successfully immersed in a natural world that they navigate with great skill and intelligence, and as individuals in a sustaining community.

Likewise, Deloria contrasts Jung's profound insights into the connectivity within consciousness of ourselves as animals, amongst other animals, sharing common roots, emerging from an overarching patterning, a differentiation of intelligences within a creative whole but then switching back into his hierarchical evolutionary frame, humans become superior, beings set apart, where what is animalic is so often seen as a retrogression to a deeper level of unconsciousness.

And so too, to dreams and visions, whereas for Jung dreams are highly individualized creators of possible meaning, often seen to be correcting the individual for lopsided development, famously their compensatory nature, for the Sioux dreams (and visions) may be this, but always have a potential practical application, and are designed to elicit key ritual and practical responses. Black Elk's extraordinary nine-year-old visions of the grandfathers were designed to impart practical knowledge that Black Elk in adult life would unfold in his healing practices and as a bearer of wisdom for his people through traumatic times. But, more often than not, were even simpler as to where to find a stray horse or a tempting buffalo herd!

At every point of his critique, Vine Deloria wants us to consider how if Jung had only gone further and been more empirically or phenomenologically grounded in his observations, he would have come closer not only to a better understanding of indigenous traditions but to a more truly embracing vision of consciousness. His profound insight into an underlying unity, manifesting in a diversity of related practices and ways of being, and the importance of differentiated approaches to knowing, of their being harmonized and balanced in social structures, including the ancestors, over time, and his deep commitment to a meaningfully unfolding cosmos whose apprehension is fundamentally religious, and where the visionary, dreaming self counts essentially, would have achieved greater clarity and more practical import.

At the crux of Deloria's critique is an invitation to think we inhabit a universe of differentiated persons, only some of whom are humans, within an unfolding mystery and that we best live when we live grounded lives in accumulating, and correcting, traditions.

At heart the divide between Deloria and Jung is do we live in a world that, to use my terminology, is iconic, where what stands over and with us, are real autonomous presences, bearing their own intrinsic meanings, within an unfolding mystery or do we live symbolically, where our default is always to imagine that what is important is what this means for me, and where the person, the other, can dangerously disappear into my own subjectivity. Likewise, is it in the very nature of, say, water to be baptismal as well as drinkable or do we live in a world where the former is a projected meaning from our own or collective subjectivity, and only the latter is truly 'real' or foundational.

Jung bestrides both possibilities and Deloria wants to coax him towards the former side! Lure him towards his mystical, magical, and, ironically, more practical side - where he is, to this reader, at least, frankly so much more interesting!

Comments

Post a Comment