When I was in my late teens, I went through a process of 'Aha' moments when addressed by a particular art form, it clicked. 'So this is what painting or poetry or music is about?' Before that my principal obsessions had been history and geography that my childhood self was going to combine in archaeology and discover lost civilisations preferably buried in remote jungles!

Some of those 'aha' moments were passed through - I cannot say I have read Orwell since school even though it was his '1984' that convicted me of the notion that novels could be read for pleasure (and enlightenment) surpassing mere duty. Some, however, have remained deeply resonant as well as blossoming out into a wider and deeper appreciation. Stravinsky's 'Rite of Spring' heard at a Sixth Form 'music appreciation class' being a case in point. It became my first record that was played endlessly on my brother's record player until my father walked in (after a week) with a five pound note and an instruction to buy another record! Stravinsky has stayed with me - and his violin concerto remains my favourite piece of music - as too he has opened a whole new world.

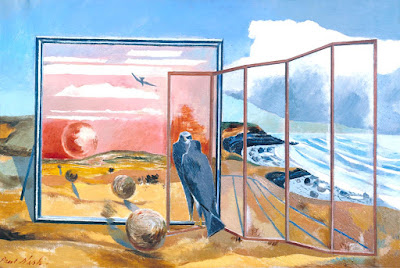

The first painting I ever saw was the one above - 'The Landscape of Dreams' by Paul Nash. It was on the cover of a Penguin Modern Classic (either a novel or a volume of poetry) though rack as I might my brain cannot remember of what title. Whatever the title, this was a book that was judged by its cover!

It is impossible now to recover what I thought on first seeing it, entangled as this is with much subsequent rumination, but I felt the strangeness of the bird who, looking through the mirror, with its back to us, is apprehended by itself but not as its reflection. The mirror is not passive but something through which you pass into a different, if related, world.

I had not realised until reading James King's excellent biography of Nash ('Interior Landscapes: A Life of Paul Nash') just how seminal this painting was to his own work and life. Here was the moment of the turning point from a world seen in division, haunted by presences that might be healing or might be destructive into a world that was enfolded in another that was affirmatively redemptive. Nash's earlier paintings were haunted by mystery, often projected as feminine in form reflecting Nash's ambivalence over a mother who gave and withheld love arbitrarily as she, sadly, slipped further into mental deterioration. In his later pictures, slowly, steadily, haunting becomes presence, mystery becomes welcoming, no longer ambivalent; and, death, which stalks Nash's art, becomes not an end but a liberation into that other world of affirmation.

This transformation is not, however, simply given. Its grace must be wrestled with and shaped. We step into a world, real in itself, yet also a product of the consciousness we bring. In this Nash was a follower of Blake. The quality of your imagination (or consciousness) determines the quality of the world you see. In the 'Landscape from a Dream', there is a three way conversation between, nature as given (the Swanage coast on the right), nature as graced through imagination (in the painting on the left) and the world beyond from which nature unfolds and into which it is enfolded (the two way mirroring at the centre). All linked by the bird as the soul and watching consciousness.

Nash wrestled with bringing each of these three elements into a redemptive whole and here states them clearly in one picture. The deep irony of his life is that as they were brought together, his own health broke asunder, and he was propelled towards the very reality beyond that he sought so diligently to show forth. His art ended for all its multiple associations with death and the beyond in affirmation of perfect balance betwixt worlds as in his 'Solstice of the Sun':

Sun and flower in dancing harmony, in perfect balancing of worlds.

Comments

Post a Comment