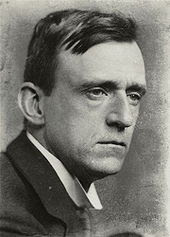

Pat Barker has made the territory of the First World War her own. First in the Regeneration trilogy she explored the impact of the war through the lens of characters historic and fictional who were treated by the psychiatrist, W.H. Rivers. Here in Toby's Room, the lens is art and its application in the work of Henry Tonks (shown here), to the reconstruction of people's physical appearance. These were the pioneering days of plastic or cosmetic surgery fuelled by the devastation wrought on the physical body by the violence of modern weapons.

Within this territory, Barker explores many of her trademark themes - the relationship between art and health. Does art provide a containing space for trauma - a cathartic place? What is the morality of disapproving of war and yet working to heal people back into that conflict? What is the right stance to war? Does pacifism break down when confronted by the actual brutalities of conflict? And, famously, her interest in sexual transgression and difference: here it is a moment of incest that haunts the relationship between sister and brother and the brother's likely homosexuality?

These themes inhabit a beautifully constructed canvas of historic realism - the coldness of houses without central heating, the prudery of landladies and the complex social dance men and women engaged in order to be alone with each other and the subtle gradations of class and both how they were being eroded and yet remained cruelly intact.

She is a highly accomplished writer whose quiet realism, without post-modern artifice, shows how a skilled storyteller, grounded in major themes, is an ever new creator of believable, seductive worlds.

I saw a small exhibition of Tonks' work in Durham (Barker's home town) and it is utterly right what she has one of her characters say that this work is both utterly utilitarian, instrumental to a purpose, and the work of no one other. Tonks was uniquely placed to develop this work being both a doctor and a professor of art. It is no criticism to suggest that, as an artist, this was his most important work. It was a work that literally re-made lives.

Comments

Post a Comment