Cecil Collins was once giving a talk critical of the state of the arts in England. He was asked by a member of the audience that if he were so critical of the art scene in England with whom was he comparing this country. Collins replied unhesitatingly, "Paradise"!

Cecil was an exceptionally gifted if idiosyncratic teacher and one of the finest artists in England in the twentieth century. Both are gifts - one in liberating the gifts of many: to be specifically artists but for many others to explore other creative opportunities. The second is to create an imaginative world that speaks to our condition - most especially a reminder, to evoke Durkheim again, of the celestial pole of our reality: a painter of paradise.

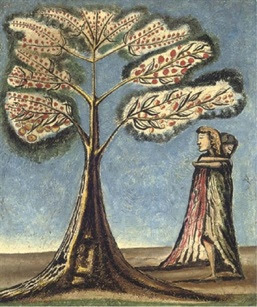

Like many artists who came to maturity in the 1930s, Collins passed through surrealism and from creating a fantasized world to the revelation of an imagined one. It was consciously 'universal'. He wanted to find a language that spoke of spirit but which did not sit with the iconography of a specific tradition. These traditions he believed had run their course - emptying of life. We had to return to the sources of archetypal life and discover new forms. He contrasted himself with his friend, David Jones, whose luminous painting depended on the forms of a historically embodied tradition: Catholicism and, thus, beautiful as they were, partook of the antique. There was always something of the early revolutionary modernist in Collins even as it was given a radical new twist.

That he saw his world was evident not only from his art but from his speech. His was a life accompanied by the angels whom he painted. His was an uncanny speech. You felt in talking to him he was in paradise, talked from it, that angels perched on the arm of your chair as you took tea!

There was too about him a steely innocence. He painted so often an image of the Fool - a traveler from another world into this one whose seeing revealed the reality of this place but left him vulnerable to its harsh realities. We do not like to be seen by purity and yet it liberates.

His art appears deeply familiar even before you learn its world. It speaks to our unsullied condition, reminding us of our 'celestial' place. It is an iconography both universal and contemporary; and, thus, timeless.

Comments

Post a Comment