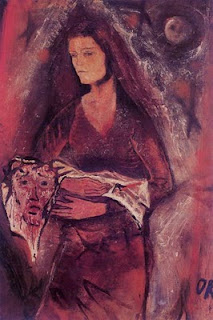

Oskar Kokoschka's 'Veronica with veil' is in London presently (from its home in Budapest) at the Royal Academy. It is hauntingly beautiful - the natural woman, earthed and present, holding the supernatural image of Christ, made as she wiped his stained face as he climbs, with the cross, to Calvary. It is a juxtaposition captured in the painting, the more naturalistic woman, the more symbolic face: the first icon of Christ.

Kokoschka called it his favourite religious painting, so the exhibit's title informs us, but that same title suggests there is a more secular explanation. Veronica was an actual woman who was cleaning Kokoschka's apartment at the time of conception. It is a curious use of the term 'secular' - that an actual woman, Veronica, might inspire an association with a known religious story (central to the mythology of Christian art's evolution) is not a 'secular' act! That the cleaner Veronica should be seen in the light of her saintly predecessor is not a 'secular' act either. The titling almost wants us to concede that the subject of the painting is the actual Veronica to which the saintly trappings are incidental - though given that Kokoschka explicitly refers to the painting as religious, grounded in an associative process with an actual Veronica, it is hard to see what this explanation is about, except perhaps a 'knee jerk' refusal of the religious!

It reminds me of a friend, the Irish artist, Patrick Pye, whose own 'arrival' as a recognised artist of distinction was arrested by his insistence on painting sacred themes which the secularised art world of Ireland refused to 'see' until finally the qualities of his art as art (irrespective of theme) wore them down to capitulation!

It caught my attention precisely because the RA's exhibit labelling is usually exceptionally good: the right kind of information, pitched at the right spot, never a false note.

This painting 'The Centaur in the Village Blacksmith's Shop' by Arnold Bocklin was the painting at the RA exhibition (http://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibitions/budapest/) that I most enjoyed. It captures (in imagination) a moment of passage, of transition from the mythological to realistic. The onlookers look on surprised at an example of a dying race come into the human realm for the practicalities of help.

It reminded me of Kathleen Rane's lament in her poem 'Wilderness' of the draining away of traditional meanings:

"I came too late to the hills: they were swept bare

Winters before I was born of song and story,

Of spell or speech with power of oracle or invocation,

The great ash long dead by a roofless house, its branches rotten,

The voice of the crows an inarticulate cry,

And from the wells and springs the holy water ebbed away."

and of the end of the Lord of the Rings when the world of men is fully established and other realms, other possibilities have passed to the west. It is a painting evocative of how a sense of displacement (the disenchantment of the world to quote Weber) was ever-present to that transitional world at the turn of the nineteenth, birth of the twentieth century.

It is my lament too - recognising another world (enfolded in this) that is not the perceived orderer of shared meaning.

Kokoschka called it his favourite religious painting, so the exhibit's title informs us, but that same title suggests there is a more secular explanation. Veronica was an actual woman who was cleaning Kokoschka's apartment at the time of conception. It is a curious use of the term 'secular' - that an actual woman, Veronica, might inspire an association with a known religious story (central to the mythology of Christian art's evolution) is not a 'secular' act! That the cleaner Veronica should be seen in the light of her saintly predecessor is not a 'secular' act either. The titling almost wants us to concede that the subject of the painting is the actual Veronica to which the saintly trappings are incidental - though given that Kokoschka explicitly refers to the painting as religious, grounded in an associative process with an actual Veronica, it is hard to see what this explanation is about, except perhaps a 'knee jerk' refusal of the religious!

It reminds me of a friend, the Irish artist, Patrick Pye, whose own 'arrival' as a recognised artist of distinction was arrested by his insistence on painting sacred themes which the secularised art world of Ireland refused to 'see' until finally the qualities of his art as art (irrespective of theme) wore them down to capitulation!

It caught my attention precisely because the RA's exhibit labelling is usually exceptionally good: the right kind of information, pitched at the right spot, never a false note.

This painting 'The Centaur in the Village Blacksmith's Shop' by Arnold Bocklin was the painting at the RA exhibition (http://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibitions/budapest/) that I most enjoyed. It captures (in imagination) a moment of passage, of transition from the mythological to realistic. The onlookers look on surprised at an example of a dying race come into the human realm for the practicalities of help.

It reminded me of Kathleen Rane's lament in her poem 'Wilderness' of the draining away of traditional meanings:

"I came too late to the hills: they were swept bare

Winters before I was born of song and story,

Of spell or speech with power of oracle or invocation,

The great ash long dead by a roofless house, its branches rotten,

The voice of the crows an inarticulate cry,

And from the wells and springs the holy water ebbed away."

and of the end of the Lord of the Rings when the world of men is fully established and other realms, other possibilities have passed to the west. It is a painting evocative of how a sense of displacement (the disenchantment of the world to quote Weber) was ever-present to that transitional world at the turn of the nineteenth, birth of the twentieth century.

It is my lament too - recognising another world (enfolded in this) that is not the perceived orderer of shared meaning.

Comments

Post a Comment